Schools get funded two ways: grants and loans. I wrote about Yonkers school district’s recent bond issuance, focusing on a recent loan they took out. Carlos Burgos, who’s running for City Council there, mentioned that a constituent was wondering where the money for schools went.

Loans like the bond issuance are only part of the story. We should look at the grants also, which come from taxes.

Yonkers City recently passed a budget that funds the district with almost $270 million. The entire school budget is something to the tune of $700 million. Where’s that money coming from?

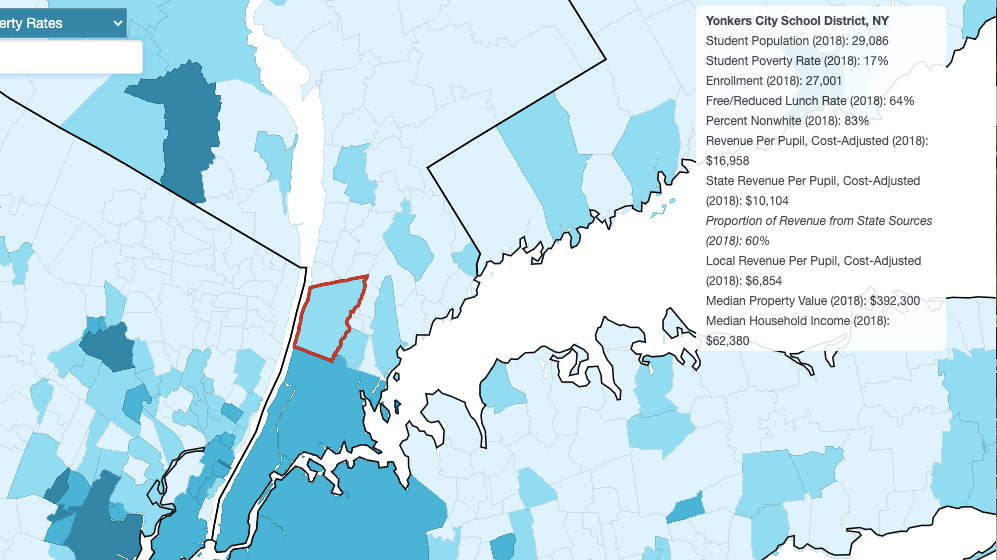

Well, two places. Yonkers only gets 38% of its school funding locally. That comes from local property taxes in the city budget. A pretty sizable 56% comes from New York state. So we have to look at the New York State budget too.

This time, let’s focus on that 38% of the local budget contribution. There’s more than enough to chew on there.

Before we get started

This whole thing can be very overwhelming. Maybe you’re not super into municipal finance. Maybe your eyes glaze over when when thinking about budgets and taxes. Before we get started on Yonkers’ local contribution to the school budget, how about we cover some basics first.

A tax is when an arm of the repressive state apparatus scoops out some money from capitalist production and spends it on something.

Schools in Yonkers, like schools pretty much everywhere in the United States, are funded through property taxes, specifically real estate: buildings, houses, land, etc.

If you own property, you pay a tax to the local and state governments, who take the money and direct it to the school district as part of the budget. (This direct connection to real estate, one of the most important forms of capital, is what makes school funding so interesting to me as a socialist.)

But that’s a very simple portrait of a gloriously complex quanty-mathy-awful process. When trying to find a metaphor for the experience of understanding this tax process, the image I keep coming back to is having a skeleton’s fingers in my brain (which is how a famously acerbic German philosopher once described reading the modern philosopher Immanuel Kant — I can confirm this is similar).

But this terrible sensation is part of the feeling of state power. So we have to let the fingers into our brains because we want the world to be better. We have to understand this stuff. Here we go.

There’s so much involved! To tax property we need numbers: prices, rates, and formulas. To tax the property, the government has to assess its value. Then it has to decide how much to tax that assessed value. That rate is called the millage rate, or the number of dollars taxed per $1,000 of assessed value.

Note, this doesn’t mean the price of the real estate on the market, or its market value. Assessed value is not what the property might go for if you wanted to buy or sell it. Rather, the assessed value is a number the government comes up with that takes into account features of the property, neighborhood, uses, exemptions, and an assessment rate. In a nice illustration of the line between base and superstructure, the assessed value is actually lower than the market value.

In Yonkers, City government assesses property value, sets the tax rate, and collects the taxes to allocate a certain amount to the schools. All of this has to follow state and federal law.

Let’s start with who’s who in this whole business.

Who’s who: assessors

There are usually a bevy of committees, commissions, and groups at both the state and local level who officially determine what the value of property is and how much to tax it. Many of these groups are led by elected officials, their staffs, and appointed officials. Let’s see who’s who in Yonkers property value assessment.

In Yonkers, the city government has an Assessment Department devoted to this task. The Assessment Department is part of the Department of Finance and Management Services, whose commissioner is John Liszewski. Here’s what he looks like:

But he oversees the whole finance department. When it comes to assessing property taxes, that falls to the City Assessor. According to a trifold I found (since it’s not listed on the website), that is David B. Jackson. Here’s Jackson being sworn in recently for another six-year term.

Mayor Spano said of Jackson that his “extensive experience in assessment administration allows us to continue to build on our efforts in providing Yonkers taxpayers with a fairer and more efficient assessment process.” What’s Jackson’s background?

He’s a property tax bureaucrat who’s been in finance departments for awhile, working for the Westchester County Tax Commission (which oversees tax assessment and collection, but doesn’t levy any taxes itself) and doing finance department stuff in Norwalk, CT and Washington, DC. He was president of something called the New York State Association of County Directors of Real Property Tax Services, a group of people who have power over property taxation in New York.

He was also super active with the International Association of Assessing Officers in DC and Connecticut, the “global leader and preeminent source of standards, professional development and research in property appraisal, assessment administration and property tax policy.” Looking at Jackson’s LinkedIn profile, he’s been overseeing the assessing of property value for a very long time.

Before we look at the numbers themselves, let’s look at who these assessors are assessing. Which properties in Yonkers get assessed?

Who’s who: the assessed

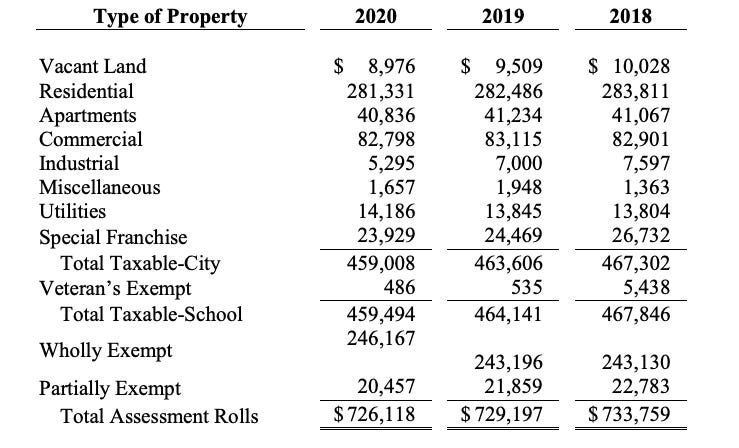

According to bond issuance, as of November of last year, Yonkers has more assessed residential property than commercial, industrial, and apartment real estate combined. Residents—home-owners—are paying a lot of these taxes to fund schools. But there’s a significant commercial and industrial tax base too.

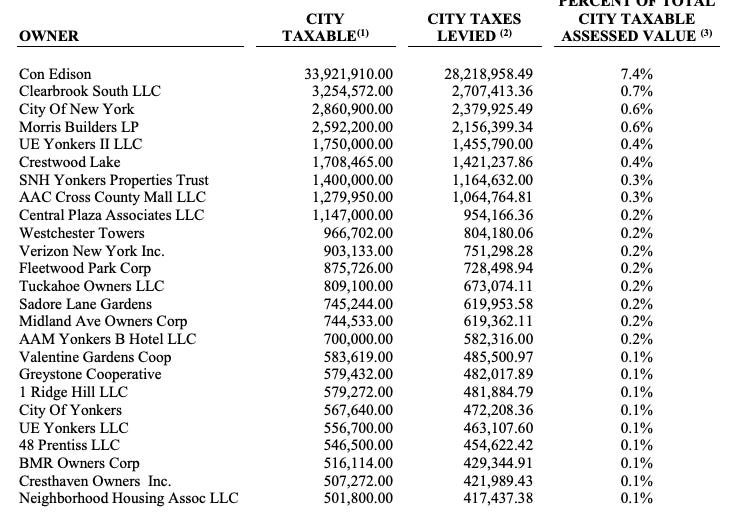

When it comes to the commercial and industrial real estate in Yonkers, let’s look at who’s got the property that’s being taxed. You can see below that Con Edison, the largest investor-owned energy company in the US, has real estate that makes up 7.4% of the city’s taxable assessed value, orders of magnitude more than any other large real estate tax payer. So while the residents pay a lot of the taxes, the largest payer is Con Ed. The next largest is Clearbrook South LLC (which seems a little weird and is something I want to look into).

The revenue

So we know who’s assessing. We know who’s getting assessed. Let’s look at the assessments themselves and the rates at which the City is taxing all this property for school funding. We can find that information in the budget.

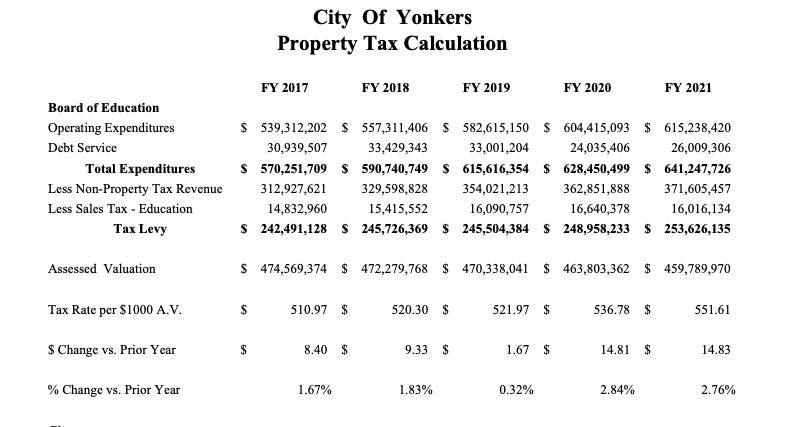

You can see in the ‘tax levy’ part of this chart that the amount the Board of Education is taking from taxes is around $254 million from an assessed valuation of almost $460 million. The millage rate is $551.51 for every $1,000 of assessed value, which is more than half and has been increasing since 2017.

If you really want to, you can go through the rolls of properties and check their assessed value and tax contributions. Here’s one document that’s almost 4500 pages long.

Local means assessment and millage

Well, there it is: local property taxes are the result of value-assessment of different kinds of real estate by a bureaucrat, the determination of a millage rate to tax them at, and then the collection of taxes for the budget.

I think the difference between assessed and market value is interesting from a socialist perspective, and of course it’s good to put faces behind these ambiguous apparatuses. If I were a leftist running for office, I’d wonder about connections between Jackson (though he seems on the level), Liszewski, and exempt properties. I’d wonder about ConEd and its role in the city as well. I’d wonder about certain neighborhoods and their parcels’ property values, if any are increasing/decreasing more than others.

But I’d also wonder about the state budget, which I can write about in the future if it’d be helpful!