Parents in Wyoming Valley School District in Pennsylvania were terrified and angry. The district sent a letter threatening to send their children to foster care. Why? Students in the district’s schools had increasing school lunch debt.

School lunch debt, believe it or not, is a real thing. It’s when students can’t pay for lunch and the school has to spot them. Typically, parents have to put money into accounts for their students, who swipe cards or give their ID numbers when getting the food in the cafeteria. If a student’s account is empty, then they technically can’t afford the meal. But the district is obligated to feed them. It’s a loss for everyone. Districts lose money and students get shamed. A blog post on this phenomenon of lunch shaming tells more harrowing anecdotes:

Imagine a high school cafeteria in which a student’s meal is taken away and thrown in the trash in front of his peers because his lunch account had an outstanding balance of $4.95. In another school, a student’s breakfast was thrown away due to a 30-cent debt. And one school denied a child breakfast even though the child’s mother told the school over the phone that she was on her way there to pay for it.

One case that made national news was in Warwick, Rhode Island. The district said students with lunch debt would only get a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for lunch. After pressure campaigns against this lunch shaming, they reversed that policy.

How does school lunch debt work structurally? What are the apparatuses involved in this situation?

Ruling class hates a free lunch

Let’s start from the ground up. How does school food finance work?

Most school districts have a food service department that manages meals. There are two ways this department can approach it’s work: in-house or outsourced. No matter which way you slice it, this is hard to do (the food puns in this literature are to die for). The School Superintendents Association, in a very thorough summary of the outsourcing debate, summarizes it this way:

operating a school district food service department is anything but simple. Even in the smallest districts, food service operations are businesses that must comply with many more rules than those in the private sector. School food service departments must operate as nonprofits, yet they need to make enough money to be self-sufficient. There are federal nutritional guidelines to follow, and the meals have to be attractive to hard-to-please consumers who are inclined to complain about “mystery meat.”

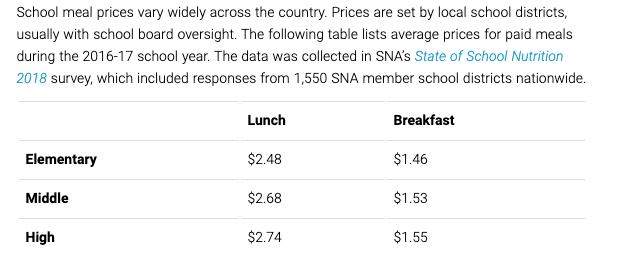

It’s a tough job. The districts also set school food prices. These meals are way cheaper than lunches that you or I might get at our workplaces. The School Nutrition Association, which tracks this kind of information, found the following average prices across K-12 levels.

I’d love to know how these prices get calculated. That’s yet another post. The more general question is: why aren’t school meals free? Wouldn’t that solve the problem?

Like most public programs, government funding for school meals has been slashed repeatedly. Laws have made it easier for private firms to provide school food too. I’m sure you’ll be shocked to hear that over the last ten years school food service has become more and more privatized, with departments opting to contract with big corporations to handle their food. I can’t find solid numbers on this score, but according to a CDC report from 2000 private companies were doing this work in 17% of US schools. That was twenty years ago, and the laws have only made it easier to go to the private sector for everything. There’s a whole other post in tracing this history, which Jennifer E. Gaddis does well.

So basically, the ruling class doesn’t want school meals to be free. They want them to be subject to capitalism like everything else. That’s why there’s school lunch debt.

But it’s not that simple, like usual. There are government programs that reimburse schools for their food service costs, particularly schools that serve poorer communities. Like everything else in the Reaganite fever-dream we’ve been living in for forty years, these programs are insufficiently funded, decentralized, and not conducive to helping people.

The US Department of Agriculture manages the National School Lunch Program, whose Community Eligibility Provision provides reimbursement for schools and districts serving a certain proportion of poor students, as defined by their families’ participation in programs like SNAP or TANF. The program serves about 30 million kids nationwide.

But you have to be super poor to get these. The School Nutrition Association says that children from families with incomes at or below 130% of the poverty level are eligible for free meals, according to the School Nutrition Association. Meanwhile, those with incomes between 130% and 185% can receive reduced-price meals. SNA indicates that 130% of the poverty level is a household income of $34,060 for a family of four and 185% is $48,470 for a family of four. Also, schools and districts have to formally register students for these programs, which requires a certification process to prove that they need it, which can sometimes go awry or not work.

Out to lunch

When it comes to lunch debt, these regulations are, well, out to lunch. The USDA makes school meal policy, which the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) administers. And right now, the law of the land is that districts can make their own policies to address school lunch debt. The legal scholar Ilana Linder calls this a “hands-off” and “decentralized” approach to the problem.

The USDA says it is ‘sensitive’ to the issue of unpaid meal charges and provides guidance, reports, and talking points for districts to deal with the problem, including how to prevent lunch shaming. They say they encourage districts to follow this guidance. This is the picture they use for the page:

A little forced, I’d say.

And hypocritical. Schools are on the hook for food costs, like I said, and the budget item is quite different than other expenses. For example, get this: according to Anique Aburuad,

the USDA does not allow schools to use federal funds to directly pay off meal debt, but it does allow such funds to be used to contract a for-profit agency to collect the debt. In a 2014 study, the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service reported that 6% of schools sent unpaid bills to collection agencies. These numbers may have risen as a result of the USDA’s 2017 requirement for schools to collect unpaid lunch debt.

So districts can use federal money to pay private companies to handle their food service, but they can’t use the same money to pay off the debt parents accrue when they can’t afford food. Some districts even end up sending these debts to collections agencies. Gross.

So what’s to be done?

Lots of policies have targeted lunch shaming, like laws in New Mexico and California. But these are treatments of a symptom rather than the disease: poverty and the inability to pay for food. People should be able to afford food for their kids. Probably the best way to address this would be to transfer control of the means of food production to cooperatives of working class people, who would then allocate grants and credit and resources to schools according to democratic procedures.

That’s a tall order, for sure. As we work towards that revolutionary policy solution, what kind of reforms might we pursue? The problem at hand is that schools don’t have enough money to pay for food. What can be done about that?

Like Arundhati Roy wrote last year, the pandemic is a portal. At the start of the shutdowns, the federal government passed a law that covered all student meal costs independent of students’ abillity to pay. The USDA extended this policy through Spring 2022. Not surprisingly, Bernie Sanders and Ilhan Omar want to make this permanent policy. These bills look good. At the state level, Texas might cancel the debt and North Dakota might pass a free lunch bill.

But if state apparatuses aren’t your thing, maybe you’re up for mutual aid organizing. School lunch debt is a great issue to take up.

A mom in Greenville, NC decided to donate leftover lunch money to her kids’ high school. Philando Castile was beloved in his community for paying off students’ school lunch debt. Organizers in North Dakota have pushed these efforts further, doing organized school lunch debt buys and winning policy demands that make it illegal to send the debt to collection agencies.